FOR THE LOVE OF VEGANS

If you’ve been around me for any length of time, you know I’m a deep end of the pool kinda kid — all-in. When I did intermittent fasting, I started with 18 hours, and before I knew it, I was doing 120-hour water fasts and lifting heavy weights as “yardstick” for what was right for me.

I have played with ketogenic and very low carb (VLC) diets since the ’90s, Atkins, Neaderthin, Paleo, the Perfect health diets, and I’ve even been a vegetarian and a vegan — in terms of the diet, I didn’t give up leather boots honestly I was experimenting with the diet for health reasons. It’s not that I like factory ranching any more than factory farming. It’s that my quest was nutritional more than purely moral or ethical. Again, when the day comes that I can get animal food level nutrition without having animals mistreated and killed, I will wholeheartedly revisit my omnivore ways.

Anyways, I respect anyone who can take on such an incredible challenge and the discipline it takes to eat an extreme diet. By extreme, I mean any diet that excludes entire categories of whole foods, regardless of their value. That just isn’t for me. I like having all the options on the table, especially what I believe to include the best options, and I don’t want to make nutrition and health any harder than it has to be. I mean, listen, animal foods range in nutritional density from one to four times, depending on where they are raised. Plants, fruits, and vegetable’s nutritional density can vary hundreds of times, and there is no way for you, the end consumer, to know. That alone should make you seriously step back and consider your options. But I will assume that if you have gone vegan, that won’t stop you, that means we need to take a look at the issues and how we can make the diet as easy and as healthy as possible.

Let’s run through the macros, nutrients, and other stuff.

Protein; this one is my favorite and, for me, the easiest. You know my thoughts on protein, you need enough, not too much and not too little, and the right way to manage it is getting enough carbs — somewhere around 4:1 carbs to protein, so we don’t waste protein by converting it into fuel.

In my opinion, plant proteins have three challenges to overcome; one — plants are typically lower in protein as a total percentage per serving than animal sources. Two, the quality of the proteins comparatively is lower, and third, the bio-availability of plant protein is lower — somewhere around half that of animal protein. There is also the issue of calories for the small amount of protein you get to be considered, especially dieting.

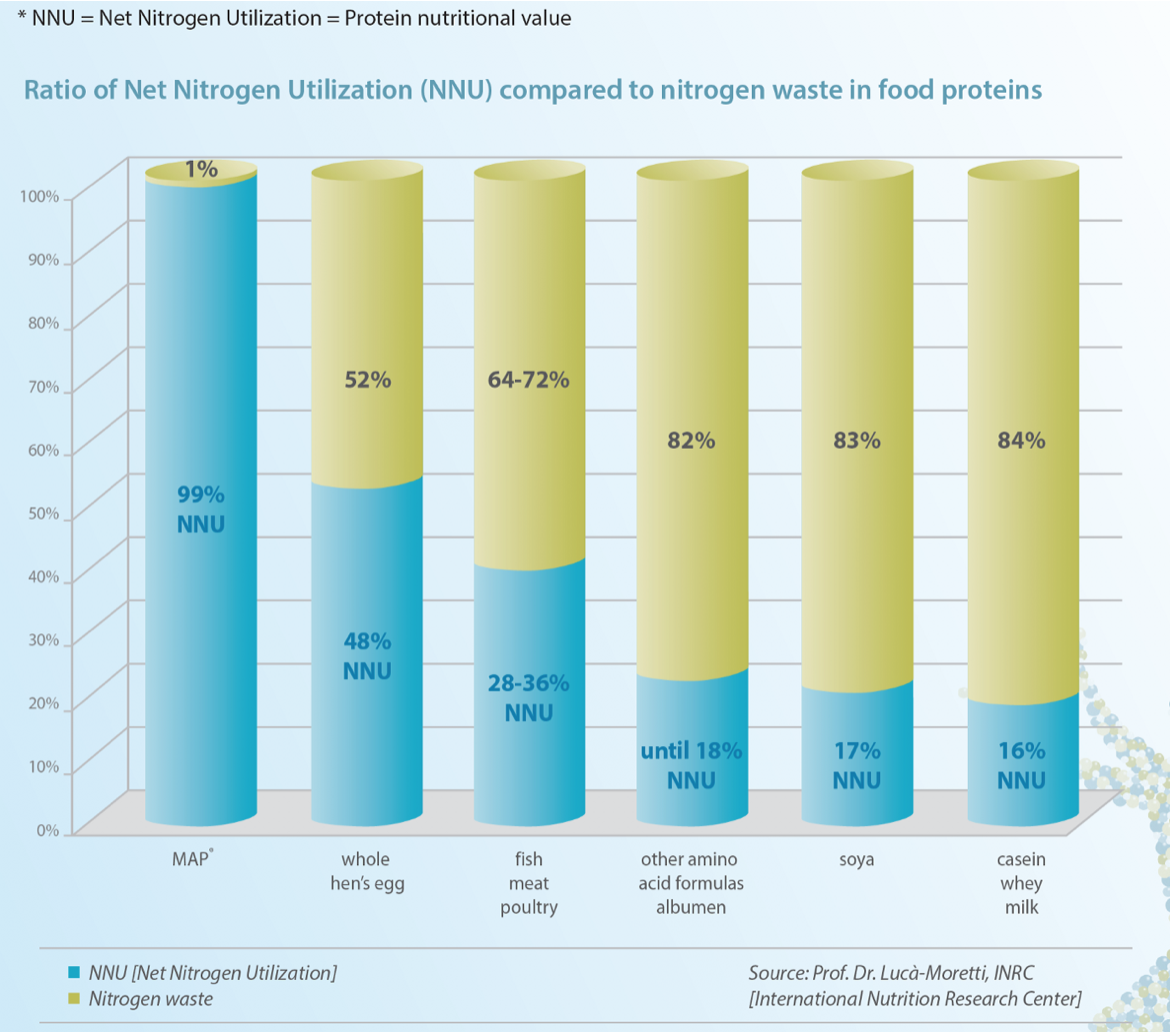

Check out these numbers using Net Nitrogen Utilization (NNU):

Eggs — 55% of the protein content is lost to ammonia.

Dairy — 70% is lost to ammonia

Meats (beef, chicken, fish) — 75% lost to ammonia.

Plant proteins — 85% or more is lost to ammonia.

If we compare similar volumes of these foods, you’ll see the challenge more clearly.

Eggs — Five large eggs (250g) is 385 kcal — 31.2g of protein, of which 55% is lost to ammonia, leaving a little more than 14g of amino acids.

Dairy — One cup (250ml) of Fat-free Skim milk is 83 kcal — 8.3g of protein, of which 70% is lost to ammonia, leaving less than 2.5g of amino acids.

Meats (beef, chicken, fish) — 250g of rib-eye steak is 510 kcal — 76.7g of protein, of which 75% is lost to ammonia, leaves you with 19.2g of amino acids.

Plant proteins — One cup (250g) of cooked lentils is 290 kcal — 22.6g of protein, which leaves less than 3.4g of amino acids.

Plant proteins — One cup (250g) of peanut butter is 1495 kcal — 55.5g of protein, which leaves less than 8.4g of amino acids.

Even when comparing the supply of essential amino acids, plants are inferior in all measures to animal proteins. But that doesn’t tell the full story either. We need to look at other bioavailability criteria such as the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) and digestible indispensable amino acid score (DIAAS).

You can find several great charts here that show the difference in bioavailability using PDCAAS and DIAAS. In all cases, except soy and tempeh, plant proteins are significantly inferior to animal proteins. But again, that isn’t the full story. Soy products are full of phytoestrogens, and estrogen is a stress hormone in both men and women. Excessive estrogen is linked to a suppressed metabolism, weight gain, and a broad range of negative hormonal impacts that affect everything, including brain function.

I think it’s pretty clear that animal proteins provide significantly more protein and of a higher quality. The milk seems lower but remember its a liquid, not a solid, so less density in all measures. Furthermore, the ones closer in protein content, like peanut butter, are 3–4x higher in calories. So if you are trying to diet and still get enough protein, this gets really challenging. At least that was my experience.

**Honestly, this is where the combination of amino acids found in AMINO PRO® really shines because it provides a great counterbalance to the abundance of particular amino acids commonly found in the vegetarian or vegan diet, ones easily shunted down pathways to stress hormones. Hence, the change is even more noticeable for them than those following other diets.

Fat: there has been lots of discussion around types of fats and linkages to disease.

The most essential thing to understand is that polyunsaturated and monounsaturated have incomplete chemical bonds and more readily oxidized. In contrast, the chemical bonds of saturated fat are all complete and hence non-reactive. A quick example is fish oil or flaxseed oil compared to coconut oil at room temperature. Very quickly, the fish oil or flaxseed oil will oxidize and go rancid. The coconut oil could stay there for a year without significant change. Cooking and health food oil manufacturers know this, and in the case of cooking oil, they treat the oil to remove the rancid scent. In the case of “health” supplements like flax or hemp oil, the bottles are dark in color to block light, and the best are stored in a chiller. Saturated fats do not require this, and considering we are like pigs rather than ruminants and do not convert fats from one type to another, it means we literally are what we eat. This has profound implications because we take a metabolic hit twice with PUFA’s, once when we eat them and store them, and again when we metabolism them taking them out of storage.

Why is this important in the context of a vegan or vegetarian diet? Because plants are significantly higher in polyunsaturated fats (PUFA) than animal products, and these are associated with diabetes, heart disease, and metabolic syndrome, including hypothyroidism.

To quote the book, In Defense of Sugar — by Joey Lott, “…research is starting to come out that demonstrates the shortcomings of all polyunsaturated fats in excess. One such study looked at the effects of feeding saturated fat versus a high omega-3 polyunsaturated fat diet to diabetic patients. What they found was that both diets resulted in an improvement in blood lipid markers. However, the polyunsaturated diet resulted in worsening blood sugar control when compared to the saturated fat diet.” This points to PUFA as one of the primary drivers of diabetes, not sugar consumption.

To quote from the book — How to heal your metabolism — by Kate Deering, [why do ranchers use…] “…corn and soy oils, both polyunsaturated fats, slow down your metabolic rate and become fattening agents. This lower metabolic rate allows these animals to gain weight faster, which allows farmers to spend less money to get their animals fat faster. We must remember farmers don’t care about having the oldest, healthiest living animals; they care about producing the fattest animals the fastest way possible.” This shows a clear linkage between PUFA consumption and suppressed metabolism.

Again, feel free to check the references at the end of this blog, but I think the evidence is clear that PUFA’s are unhealthy, especially in the quantities found in the average Western diet.

What I would do here is ensure I cooked in refined or even hydrogenated coconut oil (96% — 100% saturated fatty acids SFA respectively), and I would choose plant sources that were lowest in PUFA’s. Depending on the type of vegetarianism you practice, you could use butter or ghee, and obviously, you have a few more options

Carbohydrates: here, I think plants and, in particular, fruits have the upper hand. My issue is we don’t have a four-part stomach, so getting all the nutrition in plants isn’t possible. Sure, soaking, sprouting, pressure cooking, etc. can go a long way, but we still have anti-nutrients, lectins, phytates, etc. to contend with.

In essence, plants contain anti-nutrients (phytochemicals) used to deter predators from eating them. These phytochemicals interfere with the absorption of essential vitamins and minerals such as iron, calcium, magnesium, and zinc. So when a plant-based food says it has 50% of your RDA of zinc, that doesn’t mean you can absorb much of it.

In contrast, animal products do not contain these anti-nutrients; instead, they are rich in easily absorbed forms of vitamins and minerals. All of these make absorbing and hence benefiting from the nutrition found in plants more challenging. Further complicating this is the fact that nutritional density varies more widely in plants than in animals.

Let’s take a quick look at the difference between plant and meat vitamins and minerals availability.

Vitamin A — Is approximately 20 times more bioavailable in animal-based foods than plants. In fact, plant foods do not contain vitamin A but rather carotenoids. Furthermore, a high fiber diet, deficiency in iron, zinc, protein, or diseases like hypothyroidism, diabetes, parasites, and heavy metal poisoning negatively impact absorption and conversion. Approximately half of the population has a 50% reduction in their ability to get vitamin A from plant foods. And again, half of those people, i.e., a quarter of the total population, have that ability reduced by 75%. Add in any of the other issues mentioned previously, and you can see the challenge in getting sufficient A.

Vitamin B — Animal-based foods are the best source of B Vitamins. Especially B12, which must be supplemented by vegans and vegetarians.

Vitamin D — Plants don’t contain Vitamin D3 (the form our body needs).

Vitamin E — Plant-based foods have higher concentrations of vitamin E. And for a good reason. A plant-based diet requires additional protection from the oxidation of PUFA, which Vitamin E helps provide through its antioxidant properties.

Vitamin K — Both plant and animal foods have the K1 version; however, plants don’t have K2, which is vital for human life.

Selenium — the variation in plant sources is 100's fold, while in animals, it is between 2–5 fold — still easier to manage. For example, people living in the United States are subject to a 20-fold variation in soil selenium, while in China, they can have up to a 450-fold variation. Among plant foods, legumes, grains, nuts, and seeds tend to be useful sources of selenium, but at the cost of anti-nutrients and PUFA. The bioavailability of selenium from mushrooms, for example, is only about five percent.

Magnesium — Plant sources contain phytate, significantly reducing absorption. Soaking, sprouting, fermenting, or souring them will improve absorption. Still, high fiber and low protein diets decrease absorption, as do proton pump inhibitors, antacids, and diseases like ulcerative colitis, pancreatitis, diabetes, and anything that impairs fat absorption.

Zinc — this critical mineral is difficut to obtain in sufficiently high amounts without consuming animal products. Oysters are best with 100g giving you 16.6mg of zinc. Compared to the best plant source palm hearts supplying only 1.1mg per 100g. Considering you need 15mg, arguably twice per day, do the math…

So what would I do here? I would focus primarily on fruit consumption for nutrition and fuel. I would make sure my fruits were ripe and low fiber. If I couldn’t find fresh ripe fruit, I would use frozen — food companies freeze fruit that cannot be shipped rather than throw them out, so they are more likely to be ripe. Lastly, if neither was available, I would use canned but be aware of additional ingredients like gums and carrageenan and artificial and natural flavors.

If you really enjoy raw vegetables and salads, I would keep them to an occasional treat, not a regular diet component due to the stressful nature of fiber on the gut. You may not be aware, but we have the shortest intestinal tract of all primates, and that is believed to be because we have been cooking our foods for more than 300,000 years. Cooking breaks down food and makes nutrients more available.

If you really want more vegetables in your diet, I should cook them really well. For example, mushrooms require at least an hour of cooking to break down and should be done with the lid off, so the hydrazine doesn’t build up. Hydrazine is exceptionally toxic, even in tiny quantities. Quoting the California EPA — “has calculated a chronic inhalation reference exposure level of 0.0002 milligrams per cubic meter (mg/m3) based on liver and thyroid effects in hamsters.” Other vegetables benefit form having their fibers broken down to increase absorption and break down some of the anti-nutrients.

To be honest, I prefer fruit outside of root vegetables like potatoes and carrots, and occasionally white rice and corn for all the previously mentioned reasons.

How the Heck is this easy…?

I think a vegan diet is more challenging due to the food combinations required to get complete proteins and a significant amount of vitamin and mineral supplementation to ensure there are no deficiencies. I also believe regular blood work is even more critical to ensure you are getting enough nutrition.

If you are a vegetarian, the more flexible you are, the less challenging it becomes, and less supplementation is required.

Let me be completely honest, I am an omnivore, and I have a lot of supplements. So really, how different is that from the two choices above? I mean, just because I don’t want the added challenges doesn’t mean it isn’t doable.

Happy eating — whatever diet you choose!

References

Lucà-Moretti, M., Grandi A., Lucà E., Muratori G., Nofroni M.G., Mucci M.P., Gambetta P., Stimolo R., Drago P., Giudice G., Tamburlin N. Master Amino Acids Pattern® as substitute for dietary proteins during a weight loss diet to achieve the body’s Nitrogen Balance equilibrium with essentially no calories. Advances in Therapy; 5:282–291, 2003.

Lucà-Moretti, M., Grandi A., Lucà E., Muratori G., Nofroni M.G., Mucci M.P., Gambetta P., Stimolo R., Drago P., Giudice G., Tamburlin N., Karbalay M., Valente C., Moras G.Master Amino Acids Pattern® as sole and total substitute for dietary proteins during a weight loss diet to achieve the body’s Nitrogen Balance equilibrium. Advances in Therapy; 5:270–281, 2003.

Lucà-Moretti, M., Grandi A., Lucà E., Mariani E., Vender G., Arrigotti E., Ferrario M., Rovelli E Results of taking Master Amino Acids Pattern® as a sole and total substitute of dietary proteins in an athlete during a desert crossing. Advances in Therapy; 4:203–210, 2003.

Lucà-Moretti, M., Grandi A., Lucà E., Mariani E., Vender G., Arrigotti E., Ferrario M., Rovelli E. Comparative Results Between Two Groups of Track and Field Athletes with or without the use of Master Amino Acids Pattern® as protein substitute. Advances in Therapy; 4:195–202, 2003.

Lucà-Moretti M. A Comparative, Double-blind, Triple Crossover Net Nitrogen Utilization®Study Confirms the Discovery of the Master Amino Acid Pattern. Annals of the Royal National Academy of Medicine of Spain, Madrid; Vol. CXV: 397–416, 1998.

Vessby et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids may impair blood glucose control in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetic Medicine. 2009; 9(2): 126–133.

Boden G. Effects of free fatty acids (FFA) on glucose metabolism. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology and Diabetes. 2003; 111(3): 121–124.

J. Edward Hunter, Jun Zhang, and Penny M. Kris-Etherton, “Cardiovascular Disease Risk of Dietary Stearic Acid Compared with Trans, Other Saturated, and Unsaturated Fatty Acids: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (American Society for Nutrition), January 2010, 91 (1): 46–63.

Dr. Ray Peat, “Suitable Fats, Unsuitable Fats: Issues in Nutrition,” www.raypeat.com

Dr Ray Peat, “Unsaturated Vegetable Oil: Toxic”, www.raypeat.com

Dr. Mary Enig and Sally Fallon, “Eat Fat, Lose Fat.” Penguin Group Pusblishing, 2005.

Ancel Keys, Seven Countries: A multivariable Analysis or Death and Coronary Heart Disease. Commonwealth Fund Publications. 1980.

CE Ramsden, JR Hibbeln, SF Majchrzak, and JM Davis, “n-6 Fatty Acid-Specific and Mixed Polyunsaturated Dietary Interventions Have Different Effects on CHD Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials,” Br J Nutr, December 2010, 104(11):1586–600.

M. Borkman, DJ Chisholm, SM Furler, LH Storlien, EW Kraegen, LA Simons, and CN Chesterman. “Effects of Fish Oil Supplementation on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in NIDDM,” Diabetes, October 1989, 38(10):1314–9.

B. Vessby, B. Karlstrom, M. Boberg, H. Lithell, and C. Berne, “Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids May Impair Blood Glucose Control in Type 2 Diabetic Patients,” Diabet Med, March 1992, 9(2):126–33.

M. Anthony, “Linoleic Acid Has an Effect on Migraine Head Aches,” Clin Exp Neurol, 1978, 15:190–6.

FJ Kok, G. van Poppel, J. Melse, E. Verheul, EG Schouten, DH Kruyssen, and A. Hofman, “Do Antioxidants and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Have a Combined Association with Coronary Atherosclerosis?” Atherosclerosis, January 1991, 86(1):85–90.

Christopher Masterjohn, “Good Fats, Bad Fats: Separating Fact from Fiction,” Weston A. Price Foundation, March 24, 2012. 29. Josh and Jeanne Rubin, www.EastWestHealing.com. 30. Dr. Lita Lee, www.DrLitaLee.com, “Unsaturated Fats.” 31. Dr. Ray Peat. “Unsaturated fatty acids: Nutritionally essential, or toxic?” www.raypeat.com 32. Dr. Ray Peat. “Unsaturated Vegetable Oils: Toxic”, www.raypeat.com

Marjorie J Haskell, The challenge to reach nutritional adequacy for vitamin A: β-carotene bioavailability and conversion — evidence in humans, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 96, Issue 5, November 2012, Pages 1193S–1203S, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.034850

De Pee S, Bloem MW. The bioavailability of (pro) vitamin A carotenoids and maximizing the contribution of homestead food production to combating vitamin A deficiency. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2007;77(3):182–192. doi:10.1024/0300–9831.77.3.182

Herrero-Barbudo C, Olmedilla-Alonso B, Granado-Lorencio F, Blanco-Navarro I. Bioavailability of vitamins A and E from whole and vitamin-fortified milks in control subjects. Eur J Nutr. 2006;45(7):391–398. doi:10.1007/s00394–006–0612–0

Sauberlich HE. Bioavailability of vitamins. Prog Food Nutr Sci. 1985;9(1–2):1–33.

Jäpelt RB, Jakobsen J. Vitamin D in plants: a review of occurrence, analysis, and biosynthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:136. Published 2013 May 13. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00136

Black LJ, Lucas RM, Sherriff JL, Björn LO, Bornman JF. In Pursuit of Vitamin D in Plants. Nutrients. 2017;9(2):136. Published 2017 Feb 13. doi:10.3390/nu9020136

Hidiroglou N, Cave N, Atwall AS, Farnworth ER, McDowell LR. Comparative vitamin E requirements and metabolism in livestock. Ann Rech Vet. 1992;23(4):337–359.

McLaughlin PJ, Weihrauch JL. Vitamin E content of foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 1979;75(6):647–665.

Jiang Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72:76–90. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.035

Traber MG, Atkinson J. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43(1):4–15. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024

Schwalfenberg GK. Vitamins K1 and K2: The Emerging Group of Vitamins Required for Human Health. J Nutr Metab. 2017;2017:6254836. doi:10.1155/2017/6254836

El Asmar MS, Naoum JJ, Arbid EJ. Vitamin k dependent proteins and the role of vitamin k2 in the modulation of vascular calcification: a review. Oman Med J. 2014;29(3):172–177. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.44

Ishida Y. Clin Calcium. 2008;18(10):1476–1482.

Akbari S, Rasouli-Ghahroudi AA. Vitamin K and Bone Metabolism: A Review of the Latest Evidence in Preclinical Studies. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:4629383. Published 2018 Jun 27. doi:10.1155/2018/4629383

DiNicolantonio JJ, Bhutani J, O’Keefe JH. The health benefits of vitamin K. Open Heart. 2015;2(1):e000300. Published 2015 Oct 6. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2015–000300

McFarlin BK, Henning AL, Venable AS. Oral Consumption of Vitamin K2 for 8 Weeks Associated With Increased Maximal Cardiac Output During Exercise. Altern Ther Health Med. 2017;23(4):26–32.

van Ballegooijen AJ, Beulens JW. The Role of Vitamin K Status in Cardiovascular Health: Evidence from Observational and Clinical Studies. Curr Nutr Rep. 2017;6(3):197–205. doi:10.1007/s13668–017–0208–8